The classificatory schema 'sub-Saharan Africa', referring to 49 out of 54 of all African countries, emerged in Africa’s post-colonial era to replace racially-tinged phrases like 'Tropical Africa' and 'Black Africa' . It has, however, been labelled as a racist geopolitical signature. It has been criticised for delineating Africa based on the colonial idea that the Arab-identifying northern region was more culturally developed than countries with traditional African cultures in the south. The exclusion of Sudan from the grouping, despite it technically being below the Saharan Desert, exemplifies this. Its power regime describes it as 'Arab', along with the other four predominantly Arab states in the north. One critic has satirically proposed for a worldwide classification system using the logic behind the term 'sub-Saharan', which resulted in the relabelling of most of England as 'sub-Pennines Europe' and China, Japan and Indonesia reclassified ‘sub-Gobi Asia’.

The politicised nature of the term is further supported by its historical exclusion of South Africa. Before the full liberation of Africa in 1994, South Africa was described as the 'South African sub-continent' or 'white South Africa' instead of ‘sub-Saharan Africa’, valorising its geostrategic potential under the Apartheid regime. After the African government was restored it was

reclassified to sub-Saharan Africa and essentially relocated.

So how does the term enable a neo-colonial agenda in the context of food and water security issues?

There is an argument that the term ‘sub-Saharan Africa’ overhangs the idea that human actions are the main barrier to food and water security and instead places emphasis on its biophysical environment. The label elicits images of

"desolation, aridity, and hopelessness" in a desert ecosystem and the region has become associated with being situated below the Saharan desert.

The sentiments associated with the term 'sub-Saharan Africa' have played a role in and distracted from instances where the interventions of external actors have exacerbated food and water insecurity rather than alleviating it. Development programmes assisted by NGOs have prescribed Western ideals of development and locked some African sovereignties into neo-colonial patterns of trade and production (

Langan, 2017). The World Bank and the IMF have long been criticised for pushing the advancement of neo-liberal policies whilst limiting the influence from governments to make their own economic decisions through interventions like Structural Adjustment Programmes in the 1980s-1990s. SAPs prevented countries from decreasing dependence on primary commodity production and actively encouraged exports, mainly mono-culture crops, which continued to be a

source of crisis for many sub-Saharan African economies post-colonialism. Participating countries cut aid and slash subsidies to their rural farmers meaning that millions of low-income African families fell into food poverty.

These institutions have also been criticised for failing to direct investment in rural agricultural food production and assist in the development of "functional value chains [and] rural financial institutions" or irrigation infrastructure enabling a region-wide transition from subsistence to commercial farming practices, instead directing investment to satisfy urban demands for cheap food

(Bjornlund, Bjornlund, & Van Rooyen, 2020). Now merely

4 percent of SSA land is irrigated compared to 28 percent of northern Africa’s cultivated land (

Otsuka & Muraoka, 2017). What’s more, they failed to promote economic growth through debt relief which would’ve improved food insecurity.

Donor and corporate interventions continue to stifle growth relating to the improvement of wellbeing of poorer communities in the region. The New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition (NAFSN),

launched in 2012 by the G8 was created to offer African nations foreign investment, leading to modernization and agricultural transformation. They key trade-off for this investment, is it pushes Africa states to

implement policies that prioritise the needs of big agricultural corporations over those of small-scale farmers, including the “liberalisation of access to farmland, the promotion of certified seeds (GMOs and hybrids) and the implementation of tax reforms to facilitate private investment in agriculture”. These would prevent the informal sale of seeds which safeguard poor farmers resilient crops at affordable prices.

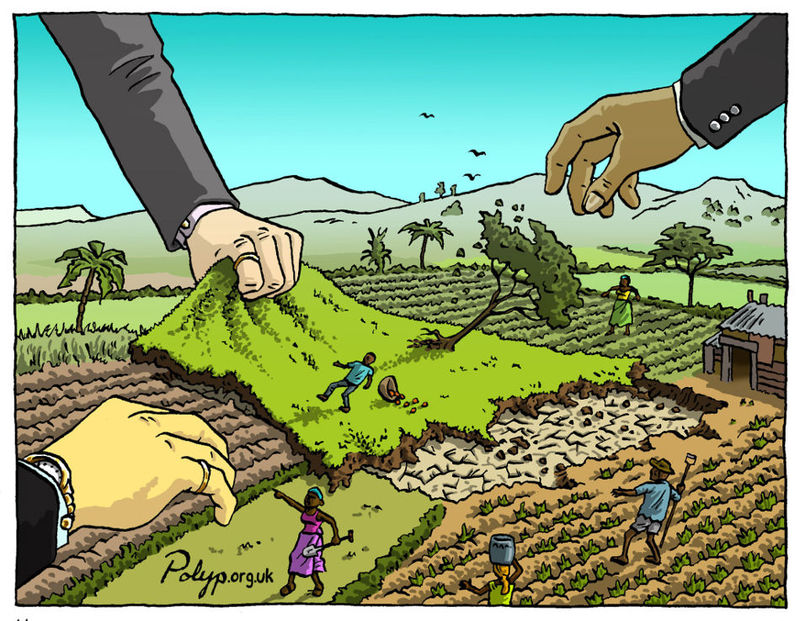

These policies put countries at

risk of land-grabbing for agribusiness at the expense of smallholder farmers through the creation of ‘agricultural corridors’. Broader discussions have taken place about whether there is a hidden agenda to corporate land acquisition, accusing them of being “water-grabs” of "virtual water", embedded in components of food and other projects. The argument goes that corporations will secure essential resources of water by financing irrigation infrastructure to store and distribute variable water sources which in turn removes water availability from small-scale production systems (

Woodhouse & Ganho, 2011). These factors led

France to pull out from the scheme in 2018.

My thoughts...

The sentiments carried by the term 'sub-Saharan Africa' have contributed to a neo-colonial agenda in the region and maybe done more harm than good in the context of food and water security. Ultimately, the term is still widely used, it is a way of gathering sources of information and it gives me freedom to explore a range of issues across the region where human and physical geography varies. I think it is essential to refrain from making generalisations about the geography of sub-Saharan Africa as a whole and to specify which sub-region, countr(y/ies), or river basin is being referenced.

Hi Bea,

ReplyDeleteSuch an interesting post, having Tunisian heritage I'd never really considered the nuances of referring to it as being in 'North' Africa - so this post definitely made me consider my own terminology!

I was curious, do you believe that interventions made my external forces relating to food and water security always detrimental, or can there also be positive implications?

Hey Juliana, that's so interesting how you've been able to reflect on your personal identity in this way :) Of course, not all of the interventions made by external forces have been negative for Sub-Saharan Africa. I have chosen to focus on detrimental examples to highlight how the force of neo-colonialism shapes food and water security issues in the region.

ReplyDeleteSome positive examples include Angola, where after the introduction of its SAP, the average the annual rate of oil exports per year increased by 8% and the IMF (1997: 8-9) claimed this was due to SAPs having liberalised economic policy by heightening the “transparency of their exports and related operations". In addition, there are many examples of where privately-funded irrigation projects by external corporations in sub-Saharan Africa have really benefited local communities by introducing simple and innovative technologies. I have written another article about this if you would like to have a look, it's about solar-powered irrigation pumps in Malawi :)